Snapshot of loneliness research

The majority of older people are not severely lonely, but current findings from ‘The Social Report 2016’ show that 10% of New Zealanders aged 65-74, and 13% of those aged over 75 feel lonely all, most, or some of the time.

This is important, not just because loneliness is painful, but because having inadequate social relationships has been shown to be as bad for health as smoking, and loneliness has been linked to increased likelihood of entering rest home care.

The good news is that there is growing information on effective interventions to reduce loneliness and social isolation, and greater understanding of how people can build resilience to prevent loneliness, or help themselves if they find that their social networks are not meeting their needs.

Covid-19 and Loneliness

The current pandemic is creating new barriers to connection throughout the world, but is also creating opportunities to learn new skills, and to connect in different ways. Here is some emerging research and expert commentary relating to social isolation and loneliness during Covid-19:

This report from New Zealand Social Wellbeing Agency: Toi Hau Tangata, identifies factors that have exacerbated loneliness and social isolation during Covid-19, and offers suggestions on how to mitigate potential ongoing health effects.

The ‘Have Our Say’ research study currently being conducted by the the Te Arai research group gives New Zealanders over 70 the opportunity to record their experiences during Covid-19 for posterity.

The European Public Health Alliance published an overview on the dangers of social isolation during a pandemic.

A recent 3-year US study showing that our need to connect is as fundamental as our need to eat. An article in the journal Scientific American article discusses the relevance of the findings to Covid-19 isolation. The preliminary report on the study is here.

Leading US experts comment here on the potential ongoing effects of Covid-19 isolation, offer recommendations on how to stay connected, and discuss the value of different forms of virtual communication during lockdown.

If you are feeling lonely

Loneliness has been described as “a distressing feeling that accompanies the perception that one’s social needs are not being met by the quantity or especially the quality of one’s social relationships.”

Feeling lonely is a common experience, and anyone can feel lonely, but it is also a sign that something needs to change. There are things we can do to help ourselves:

Often though, it helps to have some support, especially if loneliness has been going on for a long time. One simple step is to contact Age Concern on 0800 652105 to find out about their services, social activities, and volunteer opportunities. Or click here for contact details of other organisations that can help.

Tackling loneliness in communities

New Zealand

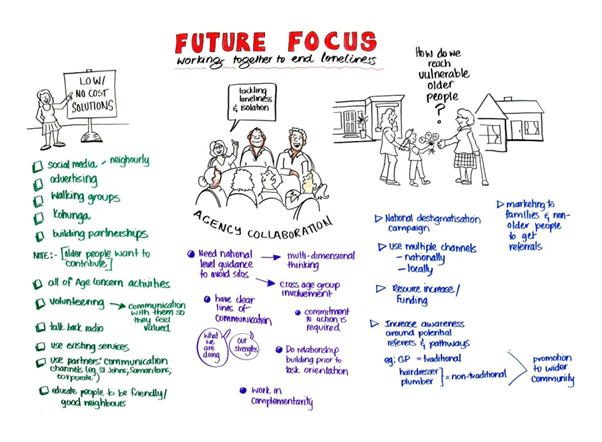

In 2018 Age Concern New Zealand held a hui with key stakeholder organisations and commissioned a Horizon poll of 1,000 adult New Zealander’s to explore barriers to social connection and identify solutions to loneliness. The findings from the Horizon poll report , and feedback from the hui (see below) inspired the formation of our coalition to end loneliness, and the development of this website.

UK

The UK Joseph Rowntree Foundation published the “Loneliness Resource Kit” , 2013 sharing the process and learning from a large-scale community action research project aimed to identify and generate actions to reduce loneliness.

Key learning was that a community development approach with staff support was highly effective, and that a relatively small investment could bring about significant citizen action.

The UK Campaign to End Loneliness reports “Promising Approaches to reducing Loneliness and Isolation” report, and ‘Promising Approaches Revisited’ provide a useful framework to understand and categorize different types of loneliness intervention, with case studies to illustrate each type. The ‘Psychology of Loneliness’ report provides guidance for designing and delivering effective campaigns and services aimed at reducing loneliness.

US

This paper by lead researcher Julian Holt-Lunstad discusses challenges around reducing the health risks of social isolation, and outlines an agenda for integrating social relationships into current public health priorities.

Prevalence and risk factors for loneliness

New Zealand

16.5% of New Zealanders felt lonely at least some of the time in 2018 compared to 16.9% in 2016, and 13.9% in 2014. A summary of loneliness stats by age, sex, ethnicity and geographic area from the 2014, 2016, and 2018 NZ General Social Survey is available here. The 2018 tables also show stats by sexual identity.

As detailed in The Social Report 2016 factors associated with higher levels of loneliness from the 2014 NZ General Social Survey were:

- Youth (15-24-year-olds were the loneliest age group, with loneliness decreasing with age before rising again for the 75+ group)

- Being female

- Being of Maori or Asian ethnicity

- Having a personal income of $30,000 or less

- Being unemployed

- Living in a sole-parent household with one or more children

- Not living in a family nucleus

- Being a migrant

- 2018 wellbeing stats indicate higher levels of loneliness for people identifying as bisexual, or “other identities”*

*A 2018 submission from the Mental Health Foundation to the government inquiry in mental health and addiction provides evidence of elevated risk of distress, suicide and addiction for the rainbow population, caused by discrimination, prejudice, stigma and social exclusion. The enquiry report is available here.

A 2017 New Zealand study of 72,000 older people who had received an InterRAI home-care assessment found that 21% of the sample (aged 82.7 years on average) were lonely, and 29% of those living alone.

Recent New Zealand research shows that Kiwis living with dementia experience a significant amount of social isolation, stigma and discrimination.

UK

‘Getting Carers Connected’, Getting Carers Connected - Carers UK a report released for UK Carers Week 2019, provides evidence of high levels of loneliness amongst carers, particularly for those lacking financial and practical support.

US

A large-scale survey of adults over 45 conducted by the AARP (American Association of Retired Persons) found that one-third of respondents were lonely. Higher rates of loneliness were associated with low income, smaller social networks, physical isolation, LGBTQ status, being an unpaid carer, being never married, divorced, separated, or being unsatisfied with a partner, and not knowing one’s neighbours. The full report is available here.

Health effects of loneliness and social isolation

The effects of social isolation and loneliness on health, are now increasingly understood.

A 2015 US meta-analytic review found that social isolation, loneliness, and living alone increased risk of early mortality by 29%, 26%, and 32% respectively, indicating that both subjective and objective social isolation pose as serious a risk to health as well-established risk factors such as smoking and obesity. Lead researcher Julianne Holt-Lunstad discusses the results of the study here.

A 2018 US study, discussed here found that loneliness increases the risk of dementia by 40%.

The cost of loneliness and social isolation

A University of Otago study published in 2019, and discussed here found that the following factors increase the likelihood of going into rest home care:

- Feeling lonely (by 20%)

- Living alone (by 43%)

- Having a stressed carer (by 28%)

- Lacking positive social interactions (by 22%)

A 2017 US study found that the federal health care program spends an average of $1,608 more a year for each older person who has limited social connections than for those who are more socially active, amounting to $6.7 billion per year.

The results of a 2013 UK survey indicate that at least 1 in 10 visits by older people to their GP appear to be motivated mainly by loneliness.

Evaluation of interventions to reduce loneliness

In October 2018, the UK “What Works for Wellbeing” centre published a review of available evidence about what works to tackle loneliness. Findings were that there is a lack of quality evidence, particularly for the under 55 age group, and that evidence relating to older adults consists generally of small-scale studies, lacking consistent definitions and measures, and not capturing the differences in effect for diverse populations. The full report and slideshow presentation are available here.

Age Concern New Zealand partnered with a research team from Auckland University on a Tranche1, National Science Challenge: Ageing Well study. The study explored how loneliness and social isolation are experienced by older New Zealanders from different cultures, and evaluated the effects of a befriending service, through recruitment of participants from Age Concern’s Accredited Visiting Service. Results are summarised in this presentation given at Age Concern New Zealand’s 2019 “Age Concerns Us” conference.

A review of evidence around intergenerational interventions published by Age UK found that positive intergenerational interactions in the workplace, in health and social care settings, in family settings, and particularly through friendships have a range of benefits including:

- Reducing ageist attitudes and behaviours

-

Increased helpful behaviours (volunteering, donating)

- Increased interest in ageing and aged care

- Lower workplace turnover

- Reduced anxiety about ageing amongst younger people